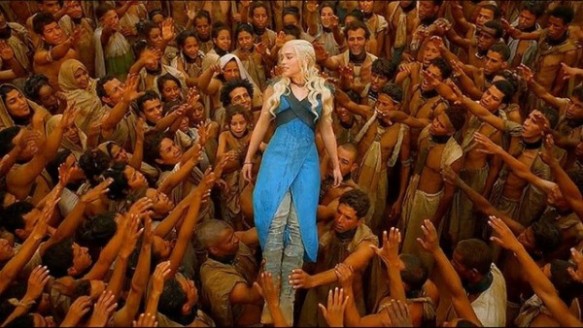

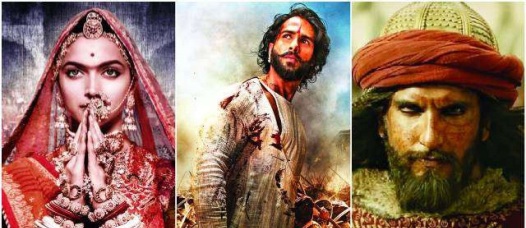

You may not have heard, since British news seems largely uninterested in covering the story, but a Bollywood film has had major attention across India this week. “Padmavat”, the story of a Hindu rani defying a Muslim ruler, has been barred from release in four of India’s states. Since November, India’s High Court has been involved to overturn the local bans amidst a violent outcry.

The film stars favourite leads Deepika Padukone and Ranveer Singh, who have previously been paired up in similar epics Ram-Leela, a 2013 Romeo and Juliet-type tragedy, and Bajirao Mastani (2015).

Why the uproar? Although specific complaints have been about the sexualised treatment of Rajput legendary figure Padmavati (the “i” was removed from the film’s name in a superficial bid to appease some, following a recommendation by the Central Board of Film Certification, who approved the film’s release uncut). In a single scene, Muslim ‘king’ Alauddin Khilji dreams of a saucy tryst with the revered beauty Padmavati, the depiction of which has outraged Hindus across India.

To be clear, the film is not, strictly speaking, a romantic picture. So what is the real problem?

As usual, it’s about Hindus and Muslims, who just can’t seem to get along. It’s not surprising following centuries of invasions, massacres, Partition, heated rhetoric and ongoing bloody conflict. Frustrating is the way that the two sides can’t leave history where it belongs, in the past, and work towards a future of peace and cooperation. It’s easy for me to say. But it’s also easy to do. One simply puts down the sword.

I’ve simplified: it’s not just about Hindus and Muslims. It’s also about India and Pakistan, and about women and men. Women have a pretty shit deal in both countries. Padmavati is idolised as a powerful woman, despite her act of power being sati, suicide-by-fire. In this case her self-immolation was to protect herself from being ravaged by the enemy, but almost always sati was and is an act of social pressure and culturally-imbued madness on behalf of a widow, whose death must inevitably follow that of her husband if she is to remain pure and respectful. She does not, in any real sense, feel like she has a choice. I myself have seen the red paint handprints on walls of village buildings and forts that were the historic signatures of those about to die because of men.

I would like to say that the film controversy is, in some way, in sisterhood with the powerful MeToo movement/s here in the West, but it’s not. Boil it down, and it’s still about Hindus and Muslims.

So powerful is the outrage that the as-yet unreleased film has inspired the following:

- Mass protests across large portions of the country, primarily Hindu-strong regions such as Rajasthan

- Legal attempts to ban the film, or at least censor it

- The invasion of the film set by one of India’s growing sinister caste groups, and personal attacks on the director, Sanjay Leela Bhansali

- Vandalism of cinemas who hadn’t denounced the film

- Threats of violence against the lead actress, Padukone

- The burning of effigies of Bhansali, and

- A £1m+ bounty on the heads of Padukone and Bhansali.

Bhansali has denied that the film includes such a sequence at all.

But such is the mass madness that comes with the peculiar mob mentality of some Indians. Fuelled by ignorance of the truth, validated by the belief that they are on the side of God or gods, and buoyed by centuries of bloodshed and bigotry (against both faith and gender), violence has washed across the country yet again.

Padmavati is not a historical figure, but a fictional heroine, here portrayed in a work of fiction.

Is it naive to expect sense from hordes who are lit on such fuel? Yes, obviously, but to paraphrase Lenon, I’m not the only dreamer. My India novel ‘Cycles of Udaipur‘ was a necessarily naive novel, written from the outside by someone who doesn’t have a stake in the ancient fued between Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan. Only, I do have a stake, and it is a desire for less death and suffering in the world, on behalf of humanity, and as a member of the human race I was more than happy to speak out in my own modest if offensive way.

When I passed free copies of ‘Cycles’ to my Indian and Pakistani friends I was always told that the first chapter was good. But then followed silence. The novel is about the growing pains of modern India, a grand attestation I make, with some embarrassment, through a more modest analogy of teen rabblerousers in Rajasthan. In part it is also about the romance between near-atheist Hindu boy, Shivlal, and near-irreverent Muslim girl, Mariam. Told, I hope, sweetly, but paying due respect, I also hope, to the fierce history that precedes my shallow experience with the societies involved, I expected the star-crossed romance to go by without much offense caused. My desi friends, after all, were worldly-wise and, in their small ways, irreverent of their own traditions to get involved with this gora backpacker/kafir scribbler. But their silence spoke volumes.

I make explanations for my naivety: It is naivety that will allow dreams to pave the way for future change. I make explanations but not excuses, since I was deliberately naive, and because an ‘enforced naivety’ – the choosing to forget about the things that don’t matter, in order to make things better for ourselves and our children – is what India and Pakistan need. But who am I to say this? I am a human stakeholder, that’s who.

It’s hard for me to hide my sad, weary disappointment. There is a lot of love in the people I’ve met and the places I’ve been. But passion is a double-edged sword, and it continues to threaten to slice on both swings. I hope that there can be some new peace and cooperation found once this latest scandal blows over.

—db

The BBC has given some small coverage to the controversy, here, here and here.

You can read about ‘Cycles of Udaipur’ here. 50% of profits go to Action Village India.

I strongly encourage discussion on this and related matters! Leave a comment here or email me at davidbrookesuk(at)gmail(dot)com.